The Hidden Threat: Cheating and Doping in Virtual Sports #

As sport increasingly shifts into the digital realm, the boundaries between physical and virtual competition blur. From online cycling to motorsport simulators, so-called “virtual sports” are growing rapidly, often mirroring their real-world equivalents in structure, sponsorship and prize money. Yet, as in both traditional and electronic sports (esports), integrity issues have followed as for example discussed in our recent blogpost on integrity issues in virtual cycling and triathlon.

Recent research by Dr Andrew Richardson at Newcastle University, An Updated Classification of Cheating in Esports, catalogues eleven categories and twenty-four sub-categories of cheating, hacking and doping across the competitive esports and virtual sport landscape. While much of the focus has been on esports titles such as Counter-Strike or Fortnite, the review also reveals how similar, and sometimes identical, threats are emerging in virtual sports such as virtual cycling and e-racing (simulators).

This article explores those findings, particularly the methods of cheating and doping highlighted in Richardson’s table and considers how the virtual sporting world may be uniquely exposed.

A New Taxonomy of Digital Deceit #

Richardson’s work updates the classic Yan & Randell framework of 2005, which first attempted to classify cheating in online games. The updated review spans incidents between 2007 and 2024 and identifies 44 distinct techniques ranging from software manipulation and server exploitation to pharmacological enhancement.

Although the terminology may sound technical, the categories fall into recognisable patterns:

- Player trust and moral exploitation – behaviours such as map hacking and sniffing cheats, where opponents’ positions or data packets are intercepted.

- Collusion and match-fixing – deliberate losses, kill-feeding, or teaming to boost friends’ scores or manipulate tournament results.

- Masking – concealing identity or location through virtual private networks or even artificial-intelligence bots disguised as legitimate players.

- Software and hardware modifications – wall hacks, speed or movement cheats, and the use of “aim-bots” or “trigger-bots” that automate precision shooting.

- Exploiting timing, verification and bugs – stream-sniping, ghosting, or exploiting coding errors (“glitches”) for an advantage.

- Performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) – stimulants and anabolic steroids, particularly within virtual sports where physical effort or long concentration is required.

- Purchasing or outsourcing cheating – buying ready-made hacks or even paying someone else to compete on one’s behalf, a modern digital equivalent of using an ineligible ringer.

This panorama demonstrates that cheating is no longer limited to minor in-game tweaks: it extends from software code to the human body itself.

Cheating in Virtual Sports: Beyond the Gamepad #

Virtual sports, such as e-cycling on Zwift or simulated motor racing on iRacing and Gran Turismo, blur the boundary between physical exertion and digital gameplay. Athletes train, race and are ranked within fully online ecosystems. According to Richardson, these environments are not immune to the same catalogue of manipulations—indeed, some are more vulnerable precisely because of their hybrid nature.

1. Digital Doping and the Use of Performance Enhancers #

One of the most striking inclusions in Richardson’s table is the explicit listing of stimulant use and androgenic anabolic steroids within esports and virtual sports. Substances such as Adderall and Ritalin, often prescribed for attention-deficit disorders, have been adopted by some players to maintain prolonged focus and reflexes during lengthy tournaments. In 2015, professional Counter-Strike player Kory Friesen openly admitted to using Adderall during competitions, claiming “everyone does it.”

In the realm of e-cycling, where physical performance still underpins virtual results, the boundary between digital and biological cheating collapses entirely. Richardson cites Luca Zanasca, banned in 2023 after testing positive for Stanozolol, an anabolic steroid, while competing on the Zwift and MyWhoosh platforms. Such cases echo traditional doping scandals yet unfold in living rooms rather than velodromes.

Virtual platforms have also encountered “gender doping” where athletes compete under false gender identities to gain entry to events with different physical classifications. The paper references multiple incidents within low-level Zwift races, demonstrating how the anonymity of online participation facilitates such deception.

2. Technological Tampering #

Cheating in virtual sport often extends to equipment manipulation. Richardson’s table lists cases where competitors embedded macro commands into computer mice or employed multiple devices to circumvent anti-cheat systems.

In e-cycling, hardware tampering can take subtler forms: altering power-meter calibration, falsifying body-weight data, or using bots to simulate pedalling cadence. British rider Cameron Jeffers was stripped of his national e-cycling title after purchasing a bot programme that generated artificial race data to unlock an in-game “virtual bike” with superior performance, as discussed back in our blogpost on “Threats and Issues to the Integrity of Virtual Sports and esports”. Though seemingly trivial, such digital upgrades can translate directly into podium results and sponsorship income.

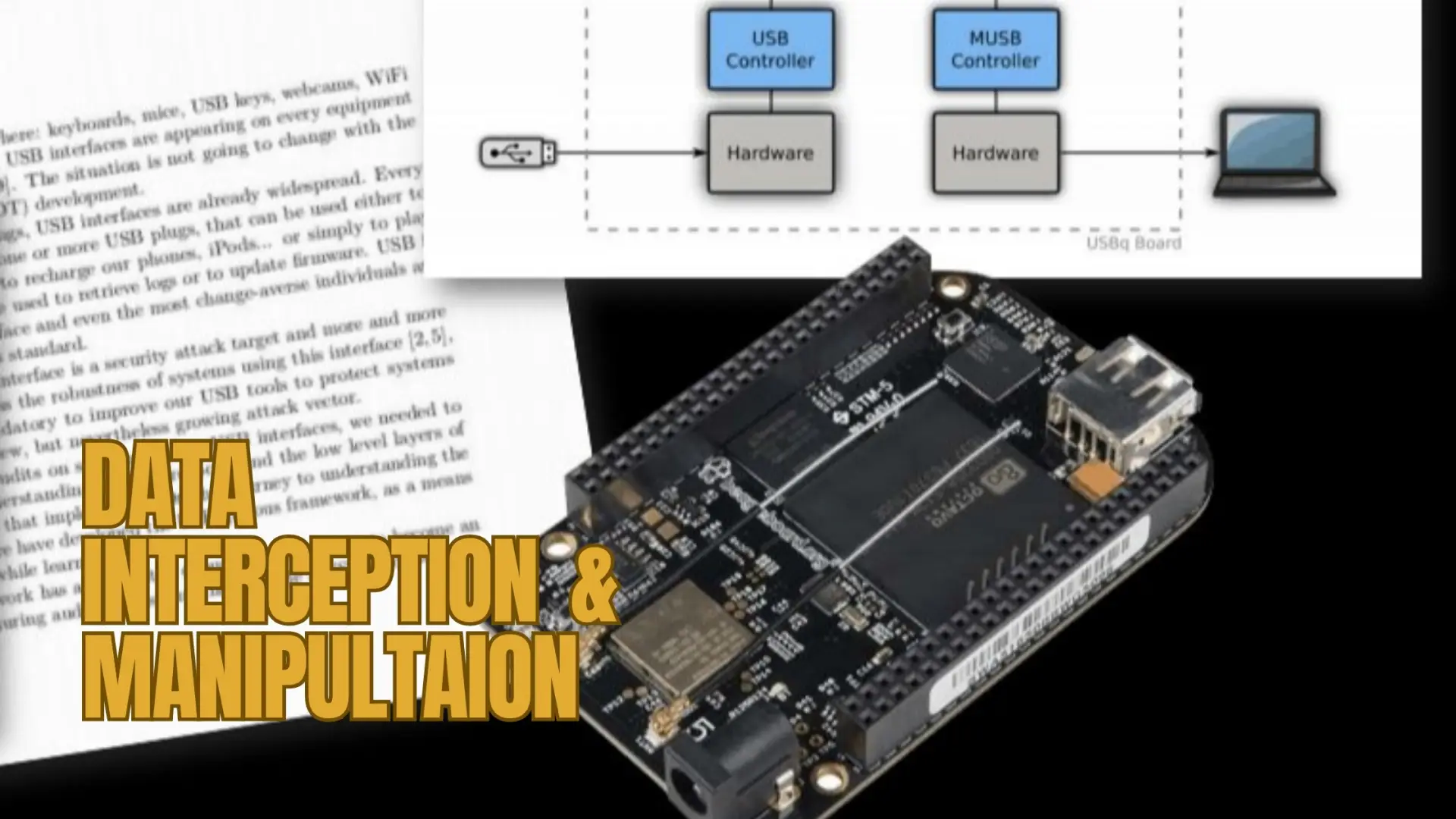

This convergence of physical sensors and digital software makes policing fairness exceedingly complex. A small technical alteration—a Bluetooth interceptor, a manipulated ANT+ signal, or an edited fit-file—can yield disproportionate advantage.

3. Software and Server Exploitation #

While physical modification characterises much of virtual-sport cheating, classic esports-style hacks also occur. Richardson documents radar glitches, map exploits and server manipulation as common across titles from PUBG to Halo.

Perhaps the most notorious recent example came from motorsport’s virtual counterpart: the Le Mans 24-Hour e-Race, where participants experienced distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that disrupted connection speeds and performance. Although no culprit was identified, such incidents illustrate the fragility of virtual competition—where the racetrack itself can be hacked. Side note: the total prize fund was US $250,000, which indicates a certain level of professionalism where digital security should be warranted.

In Halo, a professional player was suspended for using geo-filtering, a method of rerouting network traffic through selective servers to gain smoother latency or avoid stronger opponents. The principle could easily migrate to virtual sports, allowing competitors to manipulate connection quality or even conceal geographic origin in restricted events.

4. Buying Advantage #

Perhaps the most disheartening form of deception listed in Richardson’s table is the commodification of cheating. Entire criminal enterprises have emerged selling ready-made hacks for games such as Fortnite and Call of Duty Mobile, generating millions in revenue. In virtual sport, commercialised deceit can appear more benign—paying for “coaching” that is in fact remote control of one’s avatar—but the ethical breach is identical.

The accessibility of such services demonstrates that cheating is no longer the preserve of technically gifted hackers. Anyone with a credit card can now purchase unfair superiority, undermining the communal trust upon which competition depends.

Threats Specific to Virtual Sports: Why Virtual Sports Are Especially Vulnerable #

Although esports and virtual sports share overlapping ecosystems, their vulnerabilities differ in subtle but significant ways.

- Hybrid Dependence on Physical Data

Virtual sports rely on the accurate translation of physical effort into digital performance. In e-cycling or rowing simulators, power, cadence and weight data determine speed. Manipulating these inputs, whether through faulty calibration or deliberate falsification, can yield substantial advantages undetectable by traditional anti-cheat software. - Hardware Diversity and Home Environments

Unlike esports tournaments conducted on standardised equipment in controlled arenas, virtual-sport competitions frequently occur remotely, using participants’ personal setups. Variations in sensors, connectivity and environmental conditions make uniform monitoring difficult, providing fertile ground for exploitation. - Limited Oversight and Testing

Richardson notes the fragmented governance landscape: while the Esports Integrity Commission (ESIC) oversees certain titles, not all publishers or federations subscribe. Virtual sports, often organised by independent software companies rather than governing bodies, can fall through regulatory gaps. Consequently, doping controls, equipment inspections and identity verification remain inconsistent or absent. - Psychological Rationalisation

In both esports and virtual sports, the cultural acceptance of “modding” or “optimisation” fosters moral grey zones. When training platforms resemble video games, some athletes perceive manipulation as strategic ingenuity rather than fraud. The result is a creeping normalisation of “soft cheating,” from weight misreporting to data smoothing.

Threats to Virtual sports in Common with Esports #

Despite their distinctive challenges, virtual sports and esports share a common undercurrent of technological exploitation. Both depend on digital infrastructures susceptible to intrusion and manipulation, and both suffer from inconsistent international governance.

Across the spectrum, certain cheating methods transcend categorisation:

- Data interception and manipulation – whether analysing packet rates in a shooting game or altering telemetry in e-racing, information theft remains a universal vector.

- Account spoofing and ringers – from Formula E’s Daniel Abt, who let another driver race under his identity, to anonymous accounts in multiplayer arenas, identity fraud erodes authenticity across all formats.

- Match-fixing and gambling corruption – Richardson records multiple prosecutions in South Korea for StarCraft II match-fixing, mirrored in virtual sport by organised betting on online races.

- The lure of performance enhancement – whether through pharmaceuticals or algorithmic assistance, the impulse to optimise performance at any cost remains the same.

In essence, the digital and the physical are converging towards a single ethical battleground where code, chemistry and competition intersect.

Towards Integrity in a Connected Arena #

Richardson’s analysis closes with a stark warning: unless esports and virtual-sport organisations coordinate governance and enforcement, credibility will suffer. Sponsors and audiences expect fairness, and persistent scandals risk undermining public trust.

A unified global framework—similar to the World Anti-Doping Agency’s model in traditional sport—could harmonise definitions of cheating, standardise penalties, and facilitate cross-platform investigation. Education is equally vital: many competitors, especially younger ones, remain unaware that digital manipulation can carry legal as well as sporting consequences.

Technological solutions will also play a role. Advances in verification for race data, AI-driven anomaly detection, and biometric authentication may help to verify legitimate performance. Yet, as the article makes clear, no software can substitute for ethical culture. Until competitors internalise that fairness is not a limitation but a cornerstone of sport, new cheats will inevitably arise.

The Future: From Cheating to Cybercrime #

What emerges from Richardson’s comprehensive review is a picture of cheating that extends far beyond mere gaming mischief. The line between competitive advantage and criminal activity is thinning. Distributed denial-of-service attacks, data theft, and commercial cheat-selling already constitute offences under cyber-security law. As virtual and physical sports continue to merge, so too will their regulatory and legal challenges.

Ultimately, whether a player tweaks a game’s code, falsifies a power reading, or takes a stimulant to stay sharp, the moral calculus remains unchanged. The pursuit of victory through deceit corrodes both personal reputation and collective progress.

Virtual sports hold extraordinary promise: global accessibility, sustainability, and inclusivity. Safeguarding that promise will require not just anti-cheat algorithms and doping tests but a cultural shift towards integrity across every layer of digital competition.

Again, the full peer-reviewed research paper is available in the International Journal of Esports.